Lately, I’ve been writing lots of Wikipedia biographies of people who have been “castaways” on the BBC Radio programme, Desert Island Discs.

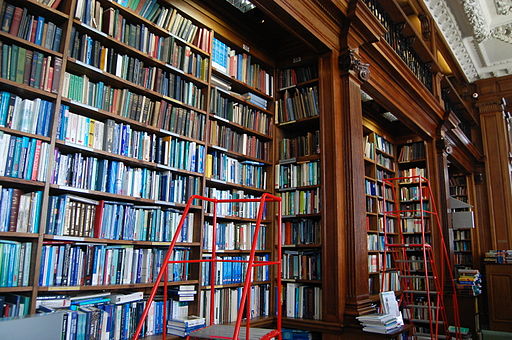

A desert island. Probably not in the North Sea

Photo by Ronald Saunders, on Flickr, CC-BY

Of all the varied people — priests, writers, musicians and others — that I’ve written about, one above all has intrigued me. Because I’ve found out less about him than any other, even though I have a full transcript of the programme.

That person is Henry Wheeler.

As I wrote on Wikipedia:

Henry Wheeler (born 1924 or 1925) was a naval signalman during World War II. The eldest in a family of six, he was from from Vernhan Grove in Bath, England, where his civilian role was as a tailor’s assistant.

He joined the Royal Navy in 1943, undertook his naval training at HMS Impregnable, went to France on the day after D-Day, and was later stationed in Rotterdam. While in Rotterdam, he had a romantic relationship with a Dutch woman, named Dine.

Shortly after the war’s end, he appeared as a “castaway” on the BBC Radio programme Desert Island Discs, on 24 November 1945, at the age of 20. He was chosen to appear as he was serving on an unspecified “small island off the European coast” — the nearest thing available to a real castaway.

And that is pretty much all anybody seems to know about him. Was he real, or a propaganda fiction, or perhaps using a pseudonym? Did return home to Bath to resume tailoring? Or did he return to marry Dine, in Rotterdam? Does anyone at Vernham Grove remember his family? Are his descendants still alive in Bath, Rotterdam or elsewhere? Indeed, is he?

Update (5 September 2014): I’m indebted to to my fellow Wikipedia editor, Andrew Davidson, who discovered that the island was Norderney; to Anne Buchanan, Local Studies Librarian at Bath Central Library, for additional material, which has now been incorporated into the article, including the fact that Henry died in 2004; and to my Twitter followers who put me in touch with her. Thank you, all.